Chapter 6

Sugaring

On a cold January evening we saw lights coming through the dark woods and up our road. Two men holding flashlights came to the door. It was Stan and our friend Ronny. Stan said he was going to start up the old Shawmut Farm Sugar House, for making maple sugar, which hadn’t been run for many years. “The place needs a lot of work,” he said, “and the trails need to have the brush and small trees cut.” I was thinking of the deep snows that year and how much trouble they were going to have getting into the back sugar bush. Stan turned to Bob and asked if he could rent Danny to collect maple sap next month. Bob said, “You’ll have to ask her. It’s her horse.” Stan turned to me and I told him, “You’ll have to hire me too, Danny and I are a team and I wouldn’t trust anyone else to work him.” Stan said “Even better, I need more hands to carry buckets.”

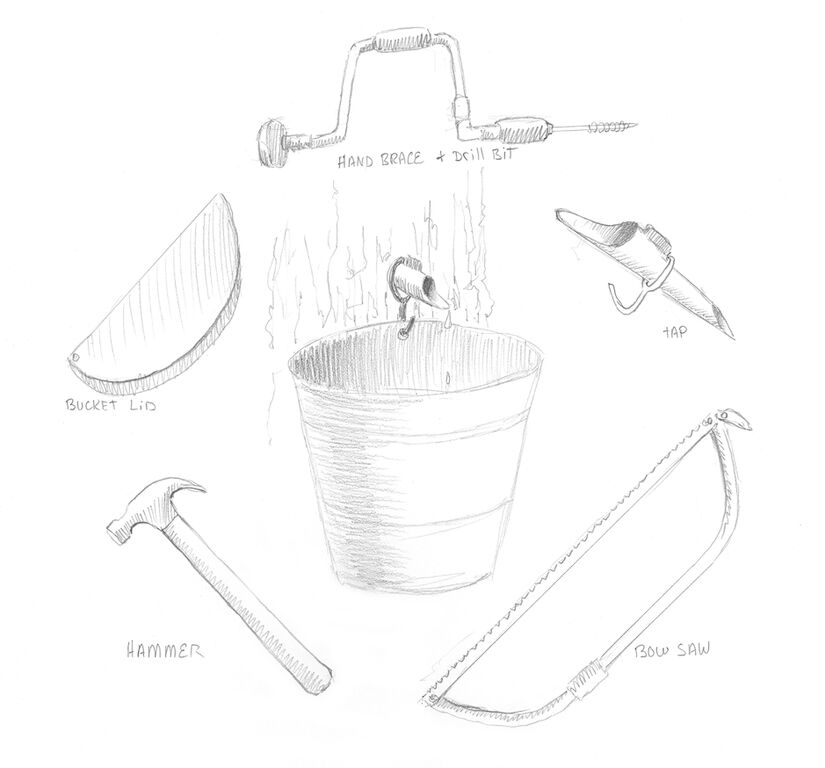

So when the days warmed up a little and the sap started to run in the middle of February, we put Danny’s harness and all his gear and feed in the truck so Bob could drive it the twelve miles to the sugar house at Shawmut Farm. I rode Danny bareback to the farm. On the way Danny heard the sound of chainsaws in the woods near the road and headed right into the woods toward the saws. He thought that’s where we must be working. I turned him back on course and kept on going to the farm. We got there just at sunset and got Danny settled in the barn at Shawmut Farm. I put his blanket on him, fed him hay and grain, and filled his water bucket. I drove home in the truck with Bob, missing Danny already. The cabin seemed so lonely with his stall empty.

The next morning, I drove back to the farm, pulling into the farmyard at 6:30. Danny nickered to me as I entered the barn. I think he was wondering if I was coming back. I fed and groomed him and cleaned his feet. Dan didn’t have shoes on for many years, but his bare hooves were great in the snow. I just put hoof ointment on them every morning and his feet never cracked. Next I rubbed liniment on his legs, especially his arthritic hocks (like elbows on the hind legs). He moved stiffly if I didn’t liniment him.

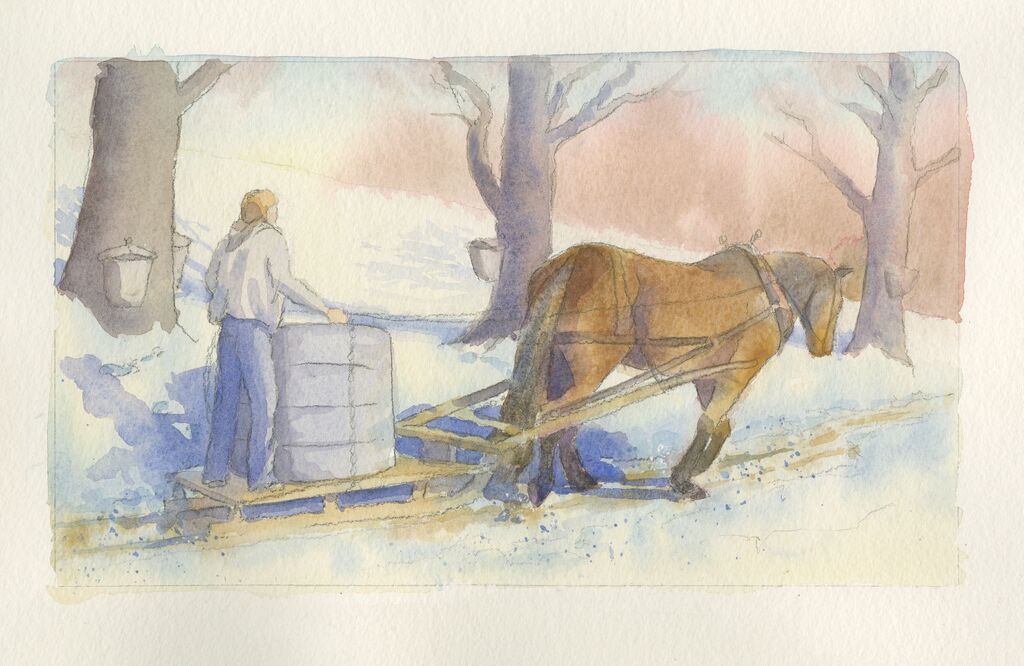

Before we could collect any sap from the trees, we had to clear the old trails and set up our taps. We loaded the sled without the tank on it, just a flat bed to haul our equipment: hand drills, taps, buckets and lids, hammer, bow saw and brush cutter. Stan, Tom, Ronny and I went down the trails through the deep snow, clearing the trails. A tree has to be at least fourteen inches in diameter to tap and larger trees can take more taps. The best sap runs under the largest limbs and the south side of a tree is especially good.

When we got to a good sugar maple we would take the hand drill and drill a hole ¾ inch by 3 inches. Then we took a tap, a five-inch-long pipe with a hook on the end to hold the bucket, and pounded it in the hole with a hammer. We then hung a bucket on the tap and put on the lid to prevent rain and bugs from contaminating the tree sap.

After two weeks of tapping, stacking wood and cleaning the old sugar house we were all set up we could begin the task of sugaring.

The first morning up at the barn I gave Danny extra grain and groomed him, he had a hard day of work ahead. I put on his collar and swung his harness up on his back. I buckled the hames on the collar and pulled the britching back over his rump. Lastly came the bridle and reins. Now we were ready to go.

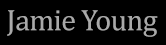

Bob and our friend Ronny had built a sled using an old single “bob” or short set of runners from a bigger sled and setting a one-hundred-and-fifty-gallon collecting tank on top of the runners. It took some adjusting of the shafts and whipple tree but finally it worked. The snow was up to Danny’s chest but he went through it easily, pulling the sled from tree to tree. The first month of sugaring is when the best grade A syrup is made, but it is harder to get to the trees because the snow is usually very deep then. That’s why Danny was so important to the operation.

Stan, Tom, and Ronny had cut many cords of wood and stacked it outside at the far end of the sugar house where the fire box doors of the boiling pan opened out. At least five big bundles of slab wood from the sawmill were stacked there too.

Collecting sap.

Every day Danny and I set out with the sled and holding tank. At each tree I would get off and empty the bucket into the holding tank. When there are cold nights and warm days the sap runs fast and the buckets fill to the rim with the sap that had dripped into the bucket overnight. Many friends and visitors came on weekends to help out and get some sweet snacks at the sugarhouse.

Danny got better and better at sugaring. He didn’t need me to guide him, as soon as he heard the collecting bucket clang on the side of the big tank he would walk to the next tree and stop, with no reining from me.

The reins were just looped on the side of the sled when Danny surprised me one day. He walked up to the next tree and flipped the lid off the bucket and drank a gallon of sap.

When we got back to the sugarhouse I told Stan the story and asked if Danny could have the sugar maple tree just outside the door of the sugar house for his reward. Stan laughed and agreed to it. There were four buckets on that big tree and every time we came in with a load I hitched him to that tree and he got to drink a sweet bucket while we unloaded.

I hitched him to that tree and he got to drink a sweet bucket.

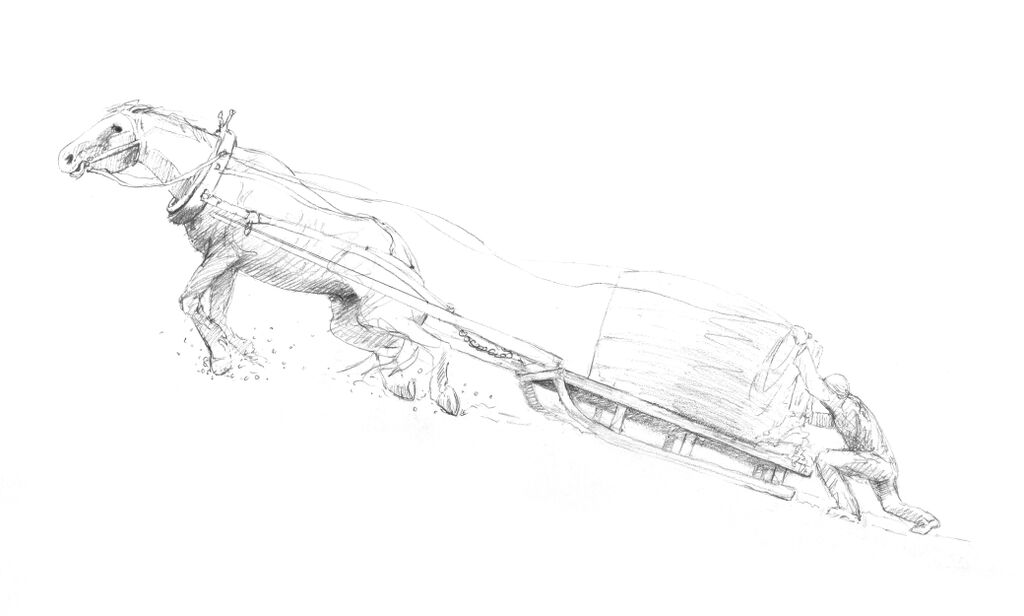

One sunny early March day we had a really good run of the best sap. All the buckets were full. We had collected a very big load at the bottom of a hillside field, which were some of our best trees. The weather was getting colder as the sun was setting. On our way back to the sugarhouse, the sap we had collected sloshed over the side of the tank and froze on the tank and sled. We started up the hill in knee-deep snow, climbing to get to the top of the field and the road. Dan was about halfway up the hill when all of a sudden he hit a patch of hard ice! The snow that had melted in the sun had now frozen into a sheet of ice right in the middle of the field. He went down on all fours and kept scrambling on his knees to get up!

I jumped off the back of the sled and started pushing with all I had. Slowly we made it to the deeper snow where Dan could get a footing. As soon as he hit the deep snow he started to take off and I had to grab onto the icy lip of the tank. The ice on the sled made for a slippery landing. As I scrambled to get back on, my foot slipped off the edge of the sled and my knee hit the sled hard, but I hung on with one foot and the reins in one hand. I pulled myself up with my arms, grasping the lip of the tank while Dan kept pulling up the hill. I couldn’t move my injured knee to get it on the sled so my leg just dangled as Dan took us the two miles back to the sugarhouse. My leg hurt so bad I wasn’t even driving him: he went by himself.

I jump off the back of the sled and started pushing with all I had.

Dan got us home to the sugarhouse. The guys came out and helped me off the sled and into the warm sugarhouse. They drained the full tank of Grade A sap into to holding tanks and put Dan in the barn for me. They also helped me take his harness off and feed him.

It was ten degrees that night so I figured I didn’t need to ice down Dan’s knees. I went home and Bob helped me put a splint on my leg. I was pretty lame but had to get back to Danny. In the morning the heat in his knees was gone so I rubbed liniment on his knees and hocks for longer than usual. Ronny helped me harness Dan and hitch him to the sled. Dan seemed to move off fine, amazingly no lameness. I was lame though. I couldn’t collect sap carrying a bucket for a while but I could drive my horse, so Stan had Ronny go with me to collect the buckets from the trees and pour them into the sled tank.

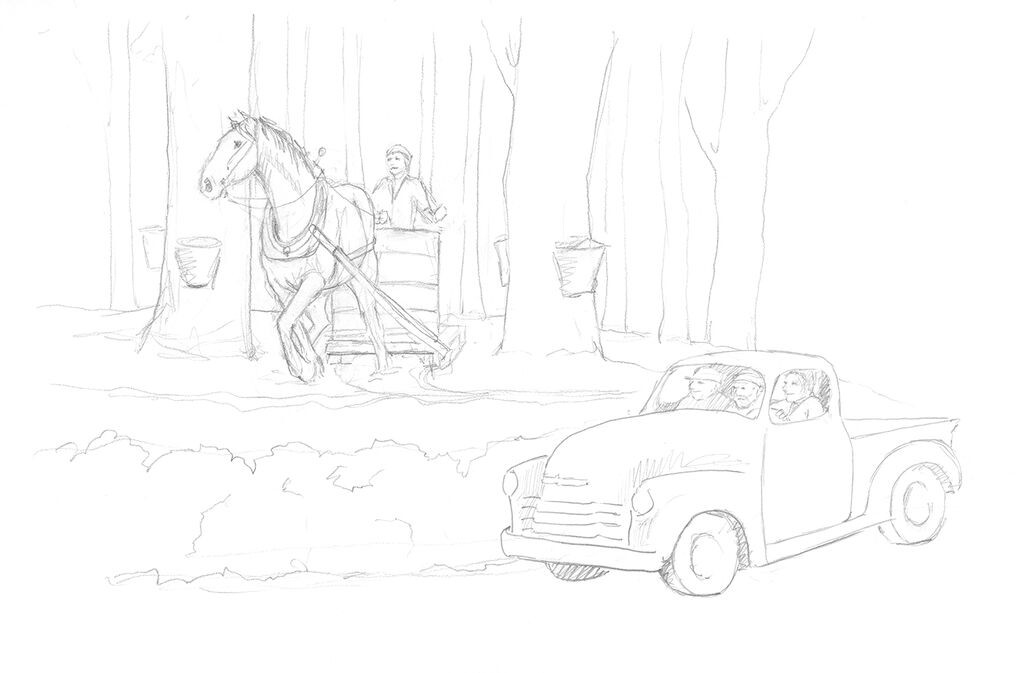

Usually Ronny and Tom collected sap from the big trees along the roads in two old trucks: a 1960 Chevy and a 1948 Willy’s Jeep pickup. We had gravity feed tubing along the roads that the extension service had told us about. Everyday they stopped at the tanks and used a pump to draw the sap up into the tanks on the trucks.

On a very sunny day after a big storm the snow banks along the road were four feet high. One of our best stands of big sugar maples was along the road. I drove Danny on top of the snow bank along the row of trees. We had about ten feet between the trees and the edge of the snow bank to work on. I collected the buckets of sap and emptied them into the big tank on the sled, one at a time. I looked up the road and there was an old pick-up truck with three old-timers watching us. Later I would learn that they had run the farm and sugared there a long time ago. In town they heard that some young folks were opening up the Shawmut Farm sugarhouse again and were using horses to collect sap. They had come for a show and Danny gave them one.

There was an old pick-up truck with three old-timers watching us.

Danny and I got to the end of the line of maples and I realized we didn’t have enough room to turn around. I didn’t know what to do. If we went over the four foot snow bank the sled would tip over and Dan would get hurt. Nervously, I asked Danny to back up just a little. He took the lead and backed between two huge trees with only a few inches on either side of the sled to spare. Then he swung himself to the other side (called fanning over) and took off in the other direction. Using knowledge he must have learned long ago, he had done a three-point turn without me guiding him. He happily trotted back to the sugarhouse with a full load of sap while I just hung on, amazed. I unloaded the sap into the holding tanks at the sugarhouse, and let Danny have his sweet treat of sap. He had more than earned it.

The three old farmers drove up to the sugarhouse. I thought they would load me up with advice but instead they congratulated me on some fine driving. I told them I couldn’t take any credit. We were in a jam and Danny got us out of there all by himself. One farmer said, “At least you were smart enough to let the horse have his head.” O.C. O’Connel was right: Danny was teaching me what I needed to know about working draft horses.

When the trees start to have a reddish color in their branches and flowers bud at the tips of the branches, it’s time to stop sugaring. Sugar season runs about five or six weeks depending on the weather. You start in the end of February making the sweetest, light (Grade A) syrup. As the season goes on the grade of syrup goes down because the trees are using the sap’s sugar to grow. It takes more and more sap to make a gallon of syrup. By the end of the season, some time around the end of March, the syrup is a dark amber or grade B.

Stan was our boss and the master boiler. If the sap is left in the tanks for more than a day it sours (turns cloudy or starts to rot) and the sap is no good. So when the weather was good with warm days and cool nights, the sap runs hard and the boiler ran almost around the clock seven days a week. Many nights Stan and Ron or Tom would be at the sugar house boiling down until three in the morning.

Tom became the fire man at the sugar house, feeding the fire under the boiling pan most of the time. He spent all day stoking the fires of the big boiling pan. The fire doors were cast iron with big dollar signs on them. The fire roared and steam filled the room. Stan could hardly be seen in all that sweet fog on the other side of the evaporator pan, only the glint of his wire rim glasses would let you know he was there. Often Stan would emerge from the sticky mist with a thermometer held high up, squinting through his steamed-up eye glasses to see how the sap was progressing. He used a hydrometer to measure how thick the syrup was at the pour-off spigot. The fourteen-foot boiling pan had baffles in it that looked like a maze and Stan used a wooden paddle to push the sap along. The sap came in one end looking like water and came out the other end a thick amber syrup.

When it was just right he opened the spigot and drained off the syrup into a large bucket with a filter on the top. Then he poured the bucket, with another clean filter, into the bottling tank. The bottler kept the syrup at 120 degrees until we poured it into gallon jugs with heat seals and caps.

There were always a few people to help drain the syrup into the cooling and bottling tanks and package the syrup from there into our gray plastic jugs. Someone usually picked up donuts to have with our maple sap tea and there were often guests available to help with that. We also had dill pickles on hand to cut the maple flavor. When you couldn’t taste the maple anymore a bite of pickle refreshed your taste buds. As the collecting crew (usually three of us), we had our own coffee mugs that we would dip into the sap pan, plunk in a tea bag and we’d have instant hot sweet tea. On big run days we helped Stan boil down at night by feeding the fire for him and bottling, afterward we would go to the local pub for dinner. When we sat at the counter our clothes would stick to the counter top and stools because of the maple steam we had been in for hours.

Around the end of March, we saw red in the tips of the maple branches and they started to bud. The season was over and it was time to finish up for the year. Danny and I went back out to all the trees and took down the buckets and pulled out the taps. The trees scar over the tap hole very quickly and stop running.

When all the equipment was back at the sugarhouse, it had to be cleaned with soap and hot water. The sap boiling pan was heated up with just water and soap in it. We used buckets of warm soapy water from the big boiling pan and scrub brushes to clean all the bottling equipment, holding tanks, and buckets.

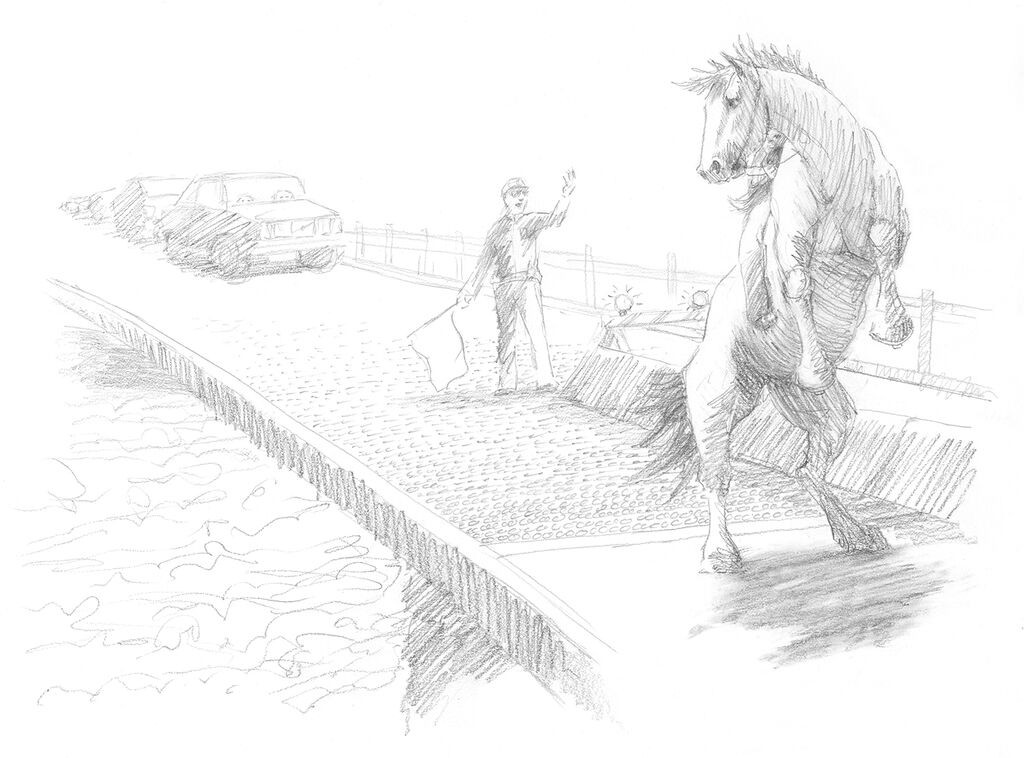

With this was all done, it was time to take Danny home. Again Bob took the harness, grooming supplies and feed home in the truck. I rode Danny back down the road through Richmond and Winchester, a beautiful ride as the spring opened up. The Ashuelot River was running hard through the center of Winchester and we had to cross an iron bridge to get to the south side of town and home. When we got to the bridge it was being repaired and a policeman was directing traffic down to one lane. Danny didn’t like the sounds of the power equipment or the flashing lights. Like many horses, he had a natural fear of water running underneath him and a fear of the iron grid he would have to walk on to cross. Add to that the flashing lights and jackhammers pounding away, it was not a good situation.

Danny also had special shoes on with metal cleats (called cog shoes) to make pulling easier for him on ice and snow, I had the farrier put the cog shoes on after our accident on the icy field. I feared his cogged shoes would catch in the grid and rip off. Danny must have sensed this too. At the edge of the bridge he reared up and spun around. He trotted a few paces back and snorted. He did this three times but wouldn’t step on the bridge. Now he had traffic stopped in both directions. The work crew had stopped the jackhammers and the policeman was waving us on.

I turned Dan to the bridge again and gave him the heels.

I’m sure Danny thought I was crazy to ask him to do such a thing. We couldn’t go around the bridge because the river was in spring flood stage and it was five miles to the next bridge. The policeman shouted, “Either cross or don’t, but you can’t hold up traffic!”

I turned Dan to the bridge again and gave him the heels. He leaped as he left solid ground as if he was going to jump the whole bridge, landing halfway across, then he nervously pranced the rest of the way. When we got to the other side, people clapped and honked their horns. He reared a little again and I let him out with the reins to trot the seven miles home with a slightly loose shoe.